Parents, students, alumni and advocacy groups say the pandemic, along with the galvanizing impact of the police killing of George Floyd has laid bare the inequities that fall most heavily on people of color.

By Richard H. Weiss

While school district administrators across the region are in the throes of trying to safely start school in a raging pandemic, they are also facing pressure to act on racial equity issues that have been festering for decades.

Parents, students, alumni and advocacy groups say the pandemic, along with the galvanizing impact of the police killing of George Floyd has laid bare the inequities that fall most heavily on people of color. While recognizing the challenges administrators face in starting classes, many see a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address what they regard as systemic racism in their districts. All have seen protest rallies or received petitions calling for change, or both. Mary Institute and St. Louis Country Day School, a private school in Ladue, has also been challenged by a group of recent graduates.

The issue is particularly acute in Clayton, which by academic measures is considered among the best in the region and the state. Clayton also enjoys a strong tax base with a business and commercial district that has burgeoned over the last half-century. But critics regard it a bastion of white privilege where well-heeled residents pay lip service to inclusion and diversity without taking strong measures.

Ten Clayton alumni from graduating classes ranging from 2014 to 2019 collaborated on a petition with 13 demands for the school district that included calls for a “zero tolerance policy” on bigotry, racism and hate speech; the hiring of Black staff members to lead anti-racism efforts; elimination of school resource police officers; and proportionate representation in honors and Advanced Placement courses.

A key organizer for the young alumni is Brandon Ford, Class of ’16, who went on to Northwestern University. “When I graduated, we had a Black superintendent and a Black director of counseling services. I still observed that Black students, particularly those in the desegregation program, were tracked out of advanced classes, guided away from elite colleges and universities, and sent to ISS (in-school suspension) for trivial reasons,” he said.

The alumni petition was followed by yet another drafted by a group of eight Clayton residents with children in district schools. Seven of the eight organizers are white; all have been involved in social justice issues for years.

Within days, the petition had 500 co-signers, and is now well above 600. The parents’ petition is assertive in setting deadlines and threatens to seek removal of administrators who are non-compliant. It calls for the district to draft an anti-racism and bias program by Sept. 1 and that it be implemented over the course of the school year.

In a preamble the group included a warning: “Should the steps outlined above fail to occur by 1 July 2021, we demand that the Board of Education begin the process of conducting a search for new administrative leadership … . We must not only hold anti-racist, anti-bias values; we must act in accordance with those values for the good of our students and our community.”

For his part, district Superintendent Sean Doherty is embracing the spirit of the petitions and protest. When Doherty saw the students’ petition and learned of the rally, he showed up and later issued a statement of contrition:

“As educators, we are responsible for ensuring our schools are safe, respectful spaces to work and learn and we failed,” he wrote.

The district organized a Black Lives Matter march through the streets of Clayton that drew more than a thousand participants.

In an interview, Doherty said he had no problem with meeting deadlines set by activists and is confident they are acting in good faith.

“We are more aligned than not aligned in this work,” Doherty said. “I feel like they gave us some different ideas to be thinking about.”

Update: The district announced that Doherty will step down at the end of the year.

‘A lot of words’

The Clayton parents group provided a joint statement when asked about Dougherty’s response to their deadlines. “The district’s response to the COVID crisis showed us how quickly they can take action when they prioritize it and demonstrates how quickly they can and should respond to the crisis of racism.”

Clayton’s School Board has also been challenged by its first and only Black member Jason Wilson. At a recent meeting, Wilson said, “I’ve been on the board for two years and I see a lot of things in the way of plans and like I said before, a lot of words around equity and things that we’re going to do, yet still we kind of wallow in the face of complacency. …We have moved the ball… if it’s a hundred yards, we’ve moved the ball inches…”

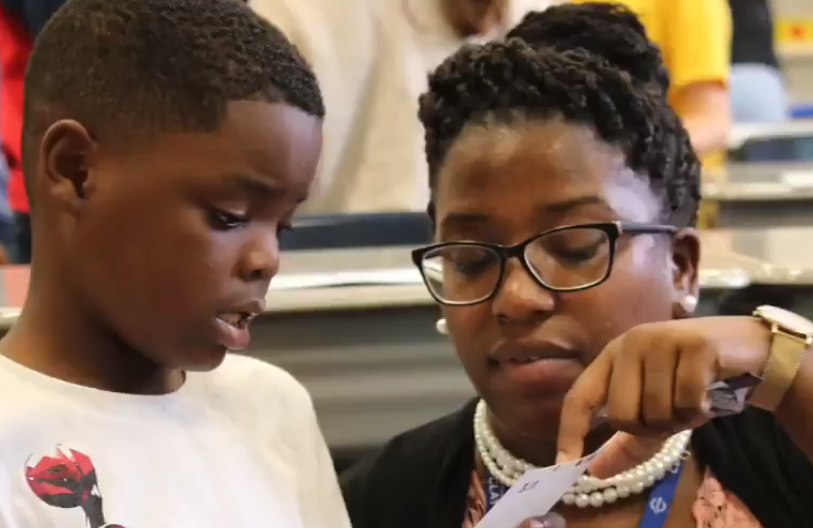

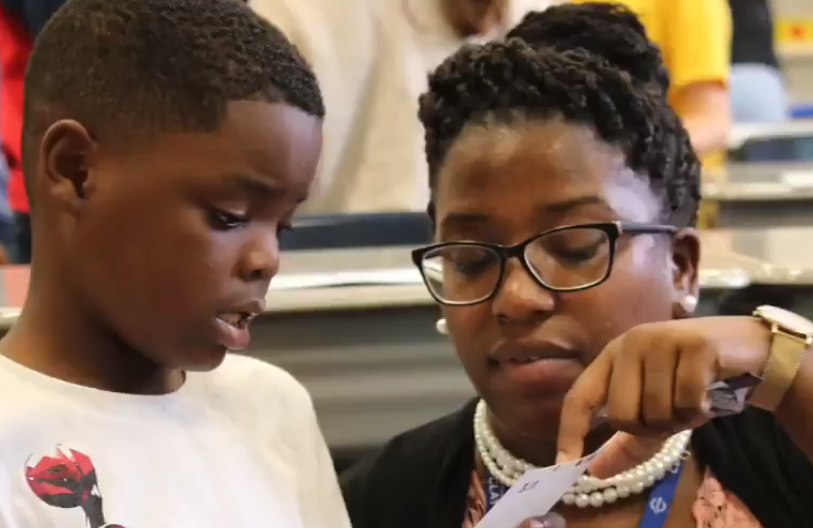

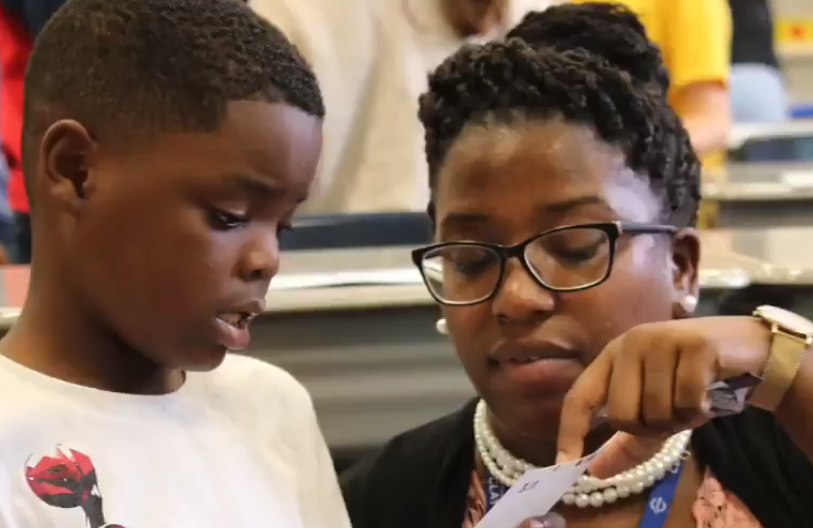

His sentiments were echoed by Jalita Johnson, who taught second grade for two years at Captain School and is leaving the district because her husband has been transferred to a job out of town. She described challenges she faced, including a series of micro-aggressions from faculty and parents. None prompted her to file a formal complaint. But she described them as a series of tiny cuts that accumulate.

As a new teacher, for example, she had not understood immediately the protocol around snack time. When parents learned of this from their children, they went straight to the principal with their concerns instead of coming to her. “That was demoralizing for me,” she said, adding that she believed that would not have happened with a white instructor. On another occasion, she said, a colleague noted that she was particularly animated in addressing her students and said that as an African-American teacher “that could be overwhelming” for some.

“As I started getting these critiques and observations, I was getting the message that I should behave as a middle-aged white woman,” Johnson said.

Johnson, 29, is a native of Macon, Ga., and the first in her family to graduate from college. She holds a master’s degree in education.

Johnson said she provided a sounding board for Clayton parents as they developed their petition, and urged them to hold administrators accountable for their words and plans.

“You can have a whole website full of lip service,” she said, “and you still have students who experience racism …and parents or teachers for that matter.”

Complacent in Lindbergh?

In the Lindbergh School District in south St. Louis County, where total non-white enrollment is 15% and African-American enrollment is just 2% among 7,000 students, activists are nonetheless passionate and increasingly impatient.

“Lindbergh has a history of silence and complacency,” wrote organizers from a group called LEAD, short for Lindbergh Equity and Diversity. “Black and brown students and families are experiencing harmful racism daily in our school district. While the district has begun some important efforts in the area of equity, Lindbergh is pacing this work at a rate that privileges the comfort of our white community members rather than the urgent safety and needs of our Black community members.”

One of LEAD’s leaders is Tara Tinnin, a district parent with three daughters. She said the group has been working with district administrators and faculty for the last few years on reform efforts. Tangible progress has been slow. With new attention being paid to racial equity issues regionally and nationwide, LEAD organizers decided an open letter to Superintendent Tony Lake and the School Board might create momentum. But unlike Clayton, the organizers made recommendations instead of demands.

The Rev. Gabrielle Kennedy, an African-American parent in the district, said she has encouraged LEAD members to be more assertive. When the group worried about whether the district would grant what they thought was a necessary permission to gather on a district parking lot Kennedy said she asked: “Is this a parade or a march? The reason that protests are disruptive is that they need to be.”

Along with serving as a pastor at Buren Chapel AME Church in Herculaneum, Mo., Kennedy is director of Faith and For the Sake of Al l, a non-profit that works with faith communities concerned with racial disparities in health and other life outcomes.

Marching in Webster Groves

In Webster Groves, superintendent John Simpson, leaned into the moment. On June 7, Webster High grads, much like in Clayton, organized a protest in Blackburn Park.

Rather than go into a defensive crouch, Simpson supported Webster Groves faculty members who organized their own rally in support of ending racist practices. He spoke at the event on June 14. Simpson said he has been working closely with African-American faculty members – mentioning particularly Hixson Middle School’s Linda Peterson, and asking white faculty to engage as well.

Simpson felt like he scored a win last month when the School Board adopted a proposal to appoint a diversity, equity and inclusion coordinator.

“We have policies that prohibit racism and discrimination, but we don’t have anything that addresses it more broadly and also more specifically. We’ve been working with staff, students, board members and administrators this summer to create that policy that will express that commitment,” Simpson said. “They are expecting more from us. And we are trying to follow suit because we need to.”

Amalia Julien, one of the Webster Groves alums from the class of 2017 who organized the student rally, applauded the move. “I feel like (the board action) is a step in the right direction,” she said. But she added more work needs to be done in addressing micro-aggressions and “creating an environment where students of color feel welcome and where hate isn’t tolerated or swept under the rug when it occurs.”

A regional approach

Activists groups that have long been involved in racial equity matters have also seized the moment. An alliance of organizations is calling for “redefining K-12” in St. Louis and has issued a list of demand s that it has put in front of every school district, charter school operators, and others educational stakeholders across the region.

One of the organizers is Charli Cooksey, CEO of WePower, an advocacy group focusing on equity issues around early childhood health and education. Cooksey said she recognizes that administrators may have their hands full at the moment opening school. Still she said there is no reason school boards cannot adopt policies that can be implemented at the first opportunity. Along with majority white districts, she is reaching out to Superintendent Kelvin Adams of St. Louis Public Schools.

Among the demands:

- Ensuring every student has access to a computer or tablet and reliable internet, and creating equitable and clear expectations for how virtual learning should be done.

- Providing individualized academic plans for all students immediately.

- Cutting ties with local police departments, disinvesting in punitive approaches to school safety and reinvesting in “evidence-based strategies that get at the root of safety challenges in schools.”

For his part, St. Louis Schools superintendent Kelvin Adams provided a series of responses, closing with a challenge of his own: “We are always willing to listen. But also, for the good of our students and our community, go a step further. Lean in to help solve the issue by seeking out resources and support.”

Alumni crusade at MICDS

Young African-American alumni at Mary Institute Country Day School are all about the right now. De ‘Ja Wood, Madi Cupp-Enyard, and Bryce Berry spent the early part of their summer organizing a rally July 19 on the grounds of the school’s Ladue campus that drew hundreds.

It came after a protracted negotiation with school administrators who were concerned the students would inflame tensions at the school and in the community. But it ended with a peaceful rally with about 250 participants and a promise from students and alumni to keep agitating until MICDS did more to address the concerns of students of color.

“We want them to do more in recruiting teachers of color and to adopt an anti-racist curriculum,” said Berry, who graduated in 2019 and is a student Morehouse College in Atlanta.

“I want to give them time to get this done. But I have to be abundantly clear. We will be expecting hard deadlines. We will be holding them accountable.”

Richard H. Weiss is founder and executive editor of Before Ferguson Beyond Ferguson, a racial equity storytelling project. More information about the activists and other stakeholders mentioned in this story can be found at https://rcjf.org/voices/